By Amita Bhakta

This blog was originally written for and published by the Rural Water Supply Network and is available here.

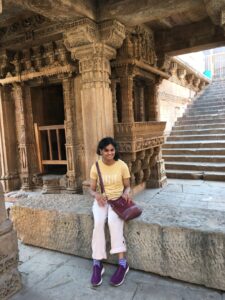

India: home to almost a fifth of the global population. Yet, its rural communities continue to face challenges in accessing water, due to overextraction depleting groundwater, poor recharge, and increased demand for water as industries expand and the rural economy grows. Ensuring water security for the future requires us to learn from the past. Across India, rural populations once met their water needs through ingenious feats of architecture in the form of stepwells (or baolis or vavs). I went to visit Adalaj Ni Vav (Rudabai Stepwell), on the outskirts of Ahmedabad, Gujarat in February 2023. In this two-part blog series, I reflect on the lessons we can learn about the significance of stepwells for India from past uses of Adalaj (part 1) and look ahead the role that stepwells could play in the future (part 2).

What are stepwells?

Stepwells are linear buildings. Steps lead down to landings with pavilions that house two shrines, and columns which make them resemble a room, followed by more steps, until reaching a cylindrical well at the bottom. The roof of one room becomes the floor of the pavilion above. Gujarat’s stepwells range from 60 to 80-feet in depth, with their upper-most landings receiving the most light, screened by walls known as Jalees to provide shade. Stepwell corridors are open to the sky except where it enters a pavilion. The terraces of stepwells are typically marked by noises and splashes as women beat clothes and scour pots, animals drink and children run around. The stepwells are referred to by landmarks (e.g. station vav), goddesses (e.g. Surya Kundi), patrons (e.g. queen) or place (e.g. Adalaj)[i].

Adalaj Ni Vav: a well with a tragic tale

Adalaj Ni Vav is a 75.3-metre-long stepwell laid out in a north-south direction. On my visit, I made my way down one of the three flights of steps arranged in a cross to enter the vav, which are attached to the main stepped corridor leading to the well at the bottom, with an octagonal opening at the top and a pavilion resting on 16 pillars with 4 built-in shrines. The vav was built between 1498-1505 by Sultan Mahmud Begada in honour of Queen Rudrarani, who he promised to marry after it was completed. When the vav was completed, Rudrarani committed suicide by jumping in to the well. Through his grief, the Sultan killed those who built it to prevent another similar vav from being built, who are buried in the graves in the nearby garden i.

Learning from Gujarat’s past links to Adalaj

Adalaj Ni Vav was once a hub for the local community until the British Raj put it and many other vavs into disuse, deeming it unhygienic and introducing taps, pumps and borewells. Rainwater harvesting enabled the community to wash their clothes and feed their animals. Travellers used the vav, built along trade routes to support India’s economic development, as a resting site[ii].

Whilst it is no longer used as a water point, Adalaj’s long-standing spiritual connections to local people can help to sustain the cultural legacy of the stepwell. There is scope to pave a way for the community to continue its traditional purpose as a place of worship. The shrine on the outer wall has long been used and maintained by local Brahmin women to the present day, who worship local goddesses for fertility, health, and family prosperity.

But, it is not just people who stand to benefit from lessons from Adalaj’s past. Birds and animals used to be attracted to the vav as a cool spot, drawn in by food left over from festivals. In an era of global challenges such as climate change, it is important to recognise that the stepwell was once a place where rich biodiversity could flourish.

Moving forward: bridging the history of Gujarat’s stepwells to the future

The history of Gujarat’s rural stepwells reflects the cultural significance they held in the past, and show a need to recognise them as previous places of sustenance and of continued spiritual value. Whilst it is unlikely that Adalaj will once again serve as a water point, it can provide a place for biodiversity to flourish, and has the potential to teach and reengage local communities with their own water management systems for future preservation, particularly in these parts of Gujarat where drilling for petroleum is creating depressions in the water table. Let’s recognise the collective memory of Gujarat’s rural stepwells as historical sites of interest and work to preserve these ancient structures for the future.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to my friend, Mona Iyer, for facilitating this field visit, and to Mahesh Popat for his brilliant support in the field. Thank you to the secretariat for their moral support for this work and to Temple Oraeki for reviewing drafts of this blog.

About the author: Amita Bhakta is a freelance consultant and co-lead for the leave no-one behind theme at the Rural Water Supply Network. She has specialised in looking at hidden issues to achieve equity and inclusion in WASH and has a keen interest in rural water heritage in India.

[i] Adalaj stepwell exhibition, Adalaj, India

[ii] National Institute of Design (1992) Adalaj village: a course documentation Ahmedabad: National Institute of Design